A little more than 10 years ago, when I still bought into the notion of the honorable American newspaper, and there wasn’t yet a lot of talk about its eminent death, I traveled to Omaha for a journalism conference where I heard a reporter from the Kansas City Star named Mike McGraw say, “I love documents,” and my career instantly came into focus.

A little more than 10 years ago, when I still bought into the notion of the honorable American newspaper, and there wasn’t yet a lot of talk about its eminent death, I traveled to Omaha for a journalism conference where I heard a reporter from the Kansas City Star named Mike McGraw say, “I love documents,” and my career instantly came into focus.

“I love studying them, skimming them, sifting through them,” he said, leaning comfortably against a podium in a hotel ballroom, in a voice of sincerity and wonder and ease.

And I understood, finally.

For four years I had worked at little daily and weekly papers in Colorado and Kansas and I’d been baffled by investigative journalism. I never knew what documents to ask for, or, when I did, I couldn’t figure out how to find stories in them.

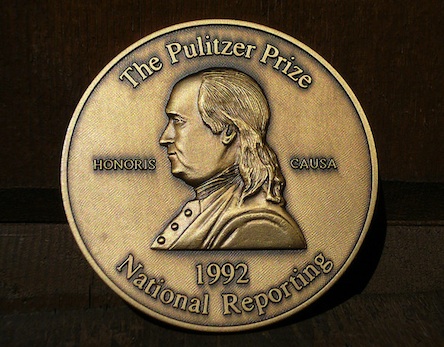

McGraw, winner of the Pulitzer Prize for national reporting in 1992, told how he’d gained access to the file room of an agency he was investigating and, feeling overwhelmed by all the information that surrounded him, said to himself something like, “OK, what am I supposed to find here?” He looked up and saw a box that had PRIVATE JET written across it in magic marker. Months later, his five-part series hit the streets, forcing reforms in the agency and winning him the Polk Prize

As I sat in the audience listening I thought, I can do that.

And I did. Within a week after the conference, I got a tip that a company south of the town where I was working as a reporter for the daily newspaper was dumping toxins into the Kansas River, the main water supply for suburban Kansas City, and state regulators were doing nothing about it.

I requested access to the files, asked myself what I was supposed to find there, and skimmed and studied and sifted through the documents, and within a few weeks my story was on the front page of the Sunday paper. The next day, state bureaucrats were scrambling to shut the polluter down. And I went on to win a Kansas Press Association award for investigative reporting.

Back then, I fantasized all the time about ascending the ranks of newspaperdom, taking a job at a big-city daily like the Chicago Tribune, Washington Post or even Kansas City Star, and kicking some big-time corrupt government ass. Daily papers were like sports teams to me, their top reporters all-stars. My Super Bowl was in April, when the Pulitzers are announced.

But I couldn’t hack it. I never made it more than six months at a daily paper. The pace would grind me down, and I’d go running back to alternative weeklies where I had time to spin long yarns, and I could cover the daily paper like a sports reporter.

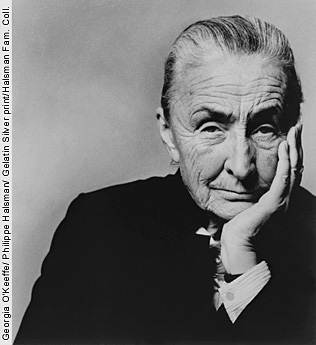

When I jumped from the little newspaper in Kansas, my final failure in daily journalism, it just so happened that I landed in Kansas City, right when a big Mike McGraw investigation was coming out. It was a multi-part story about how the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art got duped into buying a collection of fake Georgia O’Keefe water colors.

When I jumped from the little newspaper in Kansas, my final failure in daily journalism, it just so happened that I landed in Kansas City, right when a big Mike McGraw investigation was coming out. It was a multi-part story about how the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art got duped into buying a collection of fake Georgia O’Keefe water colors.

He’d spent more than a year on it; I remembered him mentioning it during his talk in Omaha. The series promised an exposé of the seamy underworld of art collecting, but delivered 7,500 painfully boring words of “he said, she said,” with no gun, smoking or otherwise.

Very disappointing, but not as disappointing as McGraw’s output over the next several years, which was almost nil.

McGraw wrote just four stories over the next two years, half of them glorified obituaries.

McGraw wrote just four stories over the next two years, half of them glorified obituaries.

The most bylines he posted in any year since I moved to Kansas City was 37, according to the paper’s online database, in 2005, when he and a couple of other reporters collaborated on an investigation of the city’s corrupt housing program.

A lot of the stories were short follow-ups on the original series, reports about the government’s response to the series, as if the paper unearthed the wrongdoing in the first place and spurred the government into action.

But I’d been around long enough to know that it was the other way around. The city’s auditor had teamed up with a special investigator from HUD to make a report that revealed virtually all of the problems the paper’s series reported. So they were playing catch up, really.

One our duties at The Pitch was to report on the daily paper. In those days, the dominant theme of our coverage of the Star was laziness. At our weekly editorial meetings, we would go on and on about how the paper of record was slacking, filing half-assed stories full of evenly apportioned quotes from both sides of issues that could easily be made definitive with a little gumshoe work. Or the stories they missed altogether.

We should’ve been happy about it. The Star’s lack was our fortune; we could write the stories they missed or underreported, and we could write about their negligence.

But we believed in the paper’s honorable imperative. We believed that the Star’s slothfulness threatened the order of things in our city and region, and provided opportunities for graft, and this was terribly unsettling, at least to me.

The whole notion of the Fourth Estate was as close as I got to religion in those days.

I was self righteous about it. I would scold the Star’s reporters about it when I’d bump into them at press conferences, like when I got on their City Hall reporter for not showing up at a luncheon attended by a quorum of City Council members. I reminded her about the Sunshine Law case the paper had pursued all the way to the state Supreme Court that had put an end to a tradition of closed-door meetings in city government.

“You have an obligation to go to these things,” I said, leaning in and pointing my finger at her.

She leered back at me, as if to say, “Who the fuck are you?”

A year or so after I moved to Kansas City, the Star offered an opportunity for select readers to come and tour their newsroom and printing plant, and to attend an editorial meeting, and help decide what would go on the front page of the next day’s edition. I signed up for it without disclosing that I was a reporter for the Pitch.

And I saw him. Mike McGraw, at a desk near a window in a far corner of the newsroom, wearing a tie, with his shirt sleeves rolled up, looking very much as though he was working, even though this was one of the years when his byline appeared only twice.

I wondered how a paper could have a Pulitzer Prize winner and never get any stories out of him.

I asked him what he was working on, but he just smiled and he wouldn’t tell me.

Years later, I’ve come to understand that by that juncture in McGraw’s career he was no longer a journalist. He had become a bureaucrat in a sluggish institution of power, no different than a City Hall lifer who has become skilled at taking an hour’s worth of work and stretching into an entire week.

And in doing so, he serves as a stark and true emblem of Kansas City’s paper of record.

This column ran one year ago on KC Confidential as Miller prepared to leave KC.

Joe Miller mentions that Mike McGraw was essentially working on an article about phony pussies.

Anyone…??

Interesting stuff. Unfortunately, I’m afraid we’ve reacched the point in America where mere survival is the name of the game, be it in the newspaper industry or, since I happened to see the word “religion” in this piece, the church. As a result, many of the institutions we have either valued from a relatively young age or come to put our faith in as adults have ultimately disappointed us because we don’t see them doing the sort of things we were expecting them to do. We want our newspapers to be exposing the graft and corruption in government, afflicting the comfortable and comforting the afflicted, speaking up on behalf of those in society who really have no voice, etc., etc. And we want our churches to be feeding the hungry, clothing the naked, visiting the sick and imprisoned, etc., etc. But when these institutions and others appear to have become content with the status quo and overly complacent, we feel betrayed and with good reason. They’ve let us down. They’ve sold their very souls for thirty pieces of silver. Again, interesting stuff. Thank you, Mr. Miller, for sharing your thoughts and observations with us.

Joe Miller is the KING of selling his soul for thirty pieces of silver. He thought he was gonna be the next Lee Atwater but wound up more like jizz on Monica Lewinsky’s dress. Instead of being part of Camelot he was part of Scamalot.

Some artists have only so much creative juice in their bodies, once that is gone it is gone.